The Texas Rangers played an effective, valiant, and honorable role throughout the early troubled years of Texas. The Ranger Service has differed in organization and policy under varying conditions, demands for service, and state administrations, and it has not been of entirely unbroken continuity. However, it has existed almost continuously from the year of colonization to the present.

In 1821, Stephen F. Austin, known as the "Father of Texas," made a contract to bring 300 families to the Spanish province, which now is Texas. By 1823, probably more than 600 to 700 people were in Texas, hardy colonists from the various portions of the United States at that time, who settled not far from the Gulf of Mexico. There was no regular army to protect them, so Austin called the citizens together and organized a group to provide the needed protection. Austin first referred to this group as the Rangers in 1823, for their duties compelled them to range over the entire country, thus giving rise to the service known as the Texas Rangers.

In 1821, Stephen F. Austin, known as the "Father of Texas," made a contract to bring 300 families to the Spanish province, which now is Texas. By 1823, probably more than 600 to 700 people were in Texas, hardy colonists from the various portions of the United States at that time, who settled not far from the Gulf of Mexico. There was no regular army to protect them, so Austin called the citizens together and organized a group to provide the needed protection. Austin first referred to this group as the Rangers in 1823, for their duties compelled them to range over the entire country, thus giving rise to the service known as the Texas Rangers.

When Austin returned from his imprisonment in Mexico in 1835, a body was organized called the "Permanent Council." On October 17, 1835, Daniel Parker, a member, offered a resolution creating a corps of Texas Rangers, 25 men under the command of Silas M. Parker to range and guard the frontier between the Brazos and the Trinity; 10 men under Garrison Greenwood to work on the east side of the Trinity; and 25 men under D. B. Frazier to patrol between the Brazos and the Colorado. These Rangers were assigned to protect the frontier against the Indians until the end of the Revolution.

On November 1, 1835, the temporary "Permanent Council" reported the organization of the Rangers to the Consultation, who approved it, and on November 9, a committee of this body commissioned G. W. Davis to raise 20 more men for this new service. The Consultation was succeeded by the General Council, which on November 24, 1835, passed an ordinance providing for three companies of Rangers, 56 men to the company, each commanded by a captain, first and second lieutenants, with a major in command. The privates received $1.25 per day for "pay, rations, clothing, and horse service," and the enlistment was for one year. The Rangers acted to protect the settlements against the incursions of Indians while Sam Houston and his army defeated the troops of Santa Anna in the Battle of San Jacinto on April 21, 1836.

In December 1836, the Congress of the Texas Republic (1836-1845) passed a law providing that President Sam Houston raise a battalion of 280 mounted riflemen to protect the frontier. The term of service was to be six months. The following January a law was passed providing for a company of 56 Rangers for the frontier of Gonzales County, and a few days later other companies were provided for Bastrop, Robertson, and Milam Counties. A little later, a law was signed for two more companies for the protection of San Patricio, Goliad, and Refugio Counties. It was during this period that the Texas Rangers began to make a name for themselves that spread far beyond the borders of the state.

In December 1836, the Congress of the Texas Republic (1836-1845) passed a law providing that President Sam Houston raise a battalion of 280 mounted riflemen to protect the frontier. The term of service was to be six months. The following January a law was passed providing for a company of 56 Rangers for the frontier of Gonzales County, and a few days later other companies were provided for Bastrop, Robertson, and Milam Counties. A little later, a law was signed for two more companies for the protection of San Patricio, Goliad, and Refugio Counties. It was during this period that the Texas Rangers began to make a name for themselves that spread far beyond the borders of the state.

After the Revolution and up to 1840, the Rangers were used principally for protection against the Indians, and history shows that they were very active in this service. In 1840, many battles against the Indians occurred, such as the Council House Fight in San Antonio, the raid on Linnville, and the Battle of Plum Creek.

On January 29, 1842, President Houston approved a law providing for a company of mounted men to "act as Rangers" on the southern frontier, and on July 23, he was authorized to accept the service of one company on the Trinity and Navasota. The same act provided for two companies on the southwestern frontier.

The law of January 23, 1844, authorized John C. Hays to raise a company of mounted men to act as Rangers from Bexar to Refugio Counties and westward.

Texas seceded from the Union and joined the Confederacy by action of a convention January 28, 1861, ratified February 23, 1861. While not much of the War Between the States (1861-1865) was fought on Texas soil, Texans contributed much to Confederate strength. A notable organization, Terry's Texas Rangers, was organized in Houston in 1861, and derived its name from the brilliant leadership of Colonel Benjamin Franklin Terry. Many of the Texas Rangers and former members enlisted in "Terry's Texas Rangers," and made an enviable record in the Confederate Army. Texas was readmitted to the Union on March 30, 1870.

The darkest period in the history of the organization, the Period of Reconstruction (1865-1873), was the re-regimentation of the Rangers as the "State Police". Under the administration of the Reconstructionist Governor E. J. Davis (January 8, 1870 - January 15, 1874), while charged with the enforcement of the unpopular carpetbagger laws, the State Police fell into disrepute among the war-weary citizens of Texas. Reconstruction and carpetbag rule was ended in 1873.

In May 1874, under Governor Richard Coke, the Legislature appropriated $75,000 to organize six companies of Texas Rangers, 75 to a company. They were stationed in districts at strategic points over the state in order to be on hand when ranches were raided. The service was known as the Frontier Battalion. Rangers were given the status of peace officers, whereas before this date the service was a semi-military organization.

During this era, the Ranger Service held a place somewhere between that of an army and a police force. When a Ranger was going to meet an outside enemy, for example, the Indians or the Mexicans, he was very close to being a soldier; however, when he had to turn to the enemies within his own society - outlaws, train robbers, and highwaymen, he was a detective and policeman.

The Rangers were organized into companies, but not regiments or brigades. The company was in the charge of a captain or a lieutenant and sometimes a sergeant. The headquarters was in Austin where the captains reported to the headquarters officer. Under the Republic of Texas this officer was the Secretary of War. Under the state, until 1935, he was the Adjutant General; since then, the Director of the Texas Department of Public Safety.

The Rangers' duties were not curbed by city or county boundaries, but included the whole state. Generally, the Ranger was called in where a case was considered too great a task for a local agency.

The later years of the 19th Century saw the Rangers involved in "detective" work, necessitated by a new group of violators known as fence cutters, and isolated cases of horse and cattle theft.

The Frontier Battalion was abolished in 1901. As the frontier disappeared, Ranger activities were redirected towards law enforcement among the citizens. The Ranger Service was reorganized under a new law. Each Ranger was considered an officer and was given the right to perform all duties exercised by any other peace officer. There were to be four companies of 20 men each, commanded by Captains John R. Hughes, J. H. Rogers, J. A. Brooks, and W. H. "Bill" McDonald. They were stationed either in far West Texas or along the Mexican border. The activities of the new service were similar to those of the Frontier Battalion after 1880.

Four events - the Mexican Revolution, World War I, oil booms, and prohibition - made demands on the Texas Rangers, which they could not meet. The Mexican Revolution filled the Mexican border with raiders; the World War brought with it spies, conspirators, and saboteurs; oil booms made West Texas a gathering place for gamblers and murderers; and prohibition filled it with smugglers and bootleggers. In January 1919, there was a cutback in the service to four companies of not more than 15 men. The Texas Rangers had served officially for more than a hundred years under the Governor, the Secretary of State, and the Adjutant General of Texas.

On August 10, 1935, when the Texas Legislature created the Texas Department of Public Safety, the Texas Rangers and the Texas Highway Patrol became members of this agency, with statewide law enforcement jurisdiction. The true modern-day Ranger came into being on September 1, 1935.

The Texas Rangers are the oldest law enforcement organization on the North American continent with statewide jurisdiction.

Silver Stars and Sixguns:

The Texas Rangers

not be stampeded"

That's the way the late Colonel Homer Garrison, Jr., longtime director of the Texas Department of Public Safety, once described the men who have worn the silver or gold star of the Texas Rangers, the oldest law enforcement agency in North America with statewide jurisdiction.

Rangers have a heritage that traces to the earliest days of Anglo settlement in Texas. They often have been compared to four other world-famous law enforcement agencies, the FBI, Scotland Yard, Interpol and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

Scores of books, from well-researched works of nonfiction to Wild West pulp novels to best-selling works of fiction, have been written about the Rangers. Over the years numerous movies, radio shows and television shows have been inspired by the Rangers.

The Rangers are part of the history of the Old West, and part of its mythology. Over the years, a distinct Ranger tradition has evolved.

As former Ranger Captain Bob Crowder once put it, "A Ranger is an officer who is able to handle any given situation without definite instructions from his commanding officer or higher authority. This ability must be proven before a man becomes a Ranger."

That definition worked well more than 150 years ago and still fits today. Yet, unlike years ago, today Texas Rangers have access to modern communications, which keeps them in touch with the rest of the world.

But a good horse was the only fast means of travel, and the best alibi for outlaws, in the early days of the Rangers.

Despite the long history of the Rangers, the term "Texas Ranger" did not appear officially in a piece of legislation until 1874.

- For the Common Defense

- "Bravo Too Much"

- War With Mexico

- "Rip" Ford

- Civil War

- The Frontier Battalion

- Sam Bass

- Preserving Law and Order

- One Riot, One Ranger

- Bandit Raids

- Bootleggers and Spies

- Oil!

- Frank Hamer

- Trailing Bonnie and Clyde

- Beginnings of the DPS

- Modernization

- World War II

- Keeping the Peace

For the Common Defense

The Ranger story begins many years ago. In 1823, the Father of Texas, Stephen F. Austin realized the need for a body of men to protect his fledgling colony, the land settlement effort that marked the beginning of Texas' development.

On August 5, 1823, on the back of a proclamation issued by Land Commissioner Baron de Bastrop, Austin wrote that he would "...employ ten men...to act as rangers for the common defense...the wages I will give said ten men is fifteen dollars a month payable in property..."

These men, not soldiers, not even militia, "ranged" the area of Austin's colony, protecting settlers from Indians. When no threat seemed evident, the men returned to their families and land.

Despite Austin's plan to pay a group of Rangers, the defense effort continued primarily on a voluntary basis.

By 1835, as the movement for Texas independence was about to boil over, a council of local government representatives created a "Corps of Rangers" to protect the frontier from Indians. These Rangers would be paid $1.25 a day and could elect their own officers. They furnished their own arms, mounts, and equipment.

R. M. "Three-Legged" Williamson (so nicknamed because he had a wooden leg to support a crippled limb) headed three Ranger companies led by Captains William Arrington, Isaac Burleson and John J. Tumlinson.

When Texas declared its independence from Mexico, some Rangers took part in the fighting, though most served as scouts.

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

"Bravo Too Much"

Certainly one of the most famous early-day Texas Rangers was John Coffee "Jack" Hays. He came to San Antonio in 1837 and within three years was named a Ranger Captain. Hays built a reputation fighting marauding Indians and Mexican bandits. An Indian who switched sides and rode with Hays and his men called the young Ranger Captain "bravo too much."

Hays' bravado was too much for many a hostile Indian or outlaw. In dealing with those deemed a threat to the young Republic, Hays helped establish another Ranger tradition--toughness mixed with a reliance on the latest in technology.

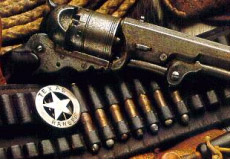

The Republic of Texas was one of the earliest customers of a New England gun maker, Samuel Colt. Colt had invented a five-shot revolver, a weapon Hays and his men used with deadly effect in defense of the Texas frontier. In fact, one of Hays' men, Samuel H. Walker, made some suggestions for improving the pistol that Colt carried out. The new weapon, which against bows and arrows or single-shot weapons was the frontier equivalent of a nuclear bomb, was called the Walker Colt.

In 1842, Walker and another former Ranger, Big Foot Wallace, took part in the ill-fated Mier Expedition, in which a group of Texans invaded Mexico. The Texans were captured and every tenth man was ordered executed.

The fate of the prisoners was determined in a drawing. Those who drew white beans lived; a black bean meant death. Walker drew a white bean. So did Wallace.

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

War With Mexico

In 1846, within a year of Texas' admission as the 28th state of the Union, the United States and Mexico were at war. Walker joined one of several Ranger companies that were mustered into federal service to function as scouts.

The Rangers fought with such ferocity in the war that they came to be called "Los Diablos Tejanos" --the Texas Devils. The luck Walker had after Mier did not hold. He was killed in the fighting.

For the next decade after the Mexican War, the Rangers existed primarily as volunteer companies, raised when the need arose and disbanded when their work was done.

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

"Rip" Ford

One of the best known Rangers of this period was John S. "Rip" Ford, whose nickname stood for "Rest in Peace." Ford--medical doctor, newspaper editor, and politician--lived up to his nickname in 1859, when Juan Nepomuceno Cortina took over the border city of Brownsville. The bandit had in mind retaking, in the name of Mexico, all of Texas below the Nueces River.

The Texas government saw it differently, and dispatched Ford and a company of Rangers to mitigate the matter. Cortina was defeated in a running fight that cost the lives of 151 of his men and 80 to 90 Texas citizens, including some Rangers.

In his memoirs, Ford later described the kind of men who served under him as Rangers:

A large proportion...were unmarried. A few of them drank intoxicating liquors. Still, it was a company of sober and brave men. They knew their duty and they did it. While in a town they made no braggadocio demonstration. They did not gallop through the streets, shoot, and yell. They had a specie of moral discipline which developed moral courage. They did right because it was right.

Still, the bloody fighting stirred passions in South Texas that were a long time in cooling.

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

Civil War

During the Civil War, with thousands of Texans off fighting with the Confederate Army, frontier protection was afforded by a "Regiment of Rangers." Even it eventually became part of the Confederate Army.

The backbone of home front security was still the volunteer "ranging" company, whose members operated on the "legal authority" of the pistols they carried on their hips or the rifle swinging in their saddle boot.

After the war, the Legislature passed a bill creating three companies of Texas Rangers, but a bill to provide funding failed. Financial support for state law enforcement in the early 1870s was sporadic. For all practical purposes, there were no Texas Rangers for nearly a decade after the war.

During this time, law enforcement was handled by a highly political and roundly hated organization known as the State Police. Texas, like other Southern states, was in the throes of reconstruction and any authority, civil or military, was distrusted. The force eventually was disbanded.

Unfortunately, the problems that had made some kind of statewide police force necessary in the first place had not disappeared along with the State Police. But Texas was changing. The military, led by war-seasoned veterans of the Union Army, was methodically ridding Texas of its Indian problem.

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

The Frontier Battalion

By the second half of the decade, the biggest threat to Texas was lawless Texans. In 1874, the Legislature created two Ranger forces to cope with the situation--the Frontier Battalion, led by Major John B. Jones and an organization called the Special Force under Captain Leander McNelly.

In five years time, the Rangers were involved in some of the most celebrated cases in the history of the Old West. Much of the fact that would later be mixed with Ranger legend occurred during the turbulent period.

Texas' deadliest outlaw, John Wesley Hardin, a preacher's son reputed to have killed 31 men, was captured in Florida by Ranger John B. Armstrong. After Armstrong, his long-barreled Colt .45 in hand, boarded the train Hardin and four companions were on, the outlaw shouted: "Texas, by God!" and drew his own pistol. When it was over, one of Hardin's friends was dead. Hardin had been knocked out cold, and his three surviving friends were staring at Armstrong's pistol. A neat round hole pierced Armstrong's hat, but he was uninjured.

Hardin served a lengthy prison sentence, only to die in a shoot-out in El Paso in 1896 shortly after his release.

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

Sam Bass

Another well-known Texas outlaw who had a run-in with Texas Rangers did not make it to prison.

Train robber Sam Bass, who had been in Texas since 1870, was confronted by four Rangers in Round Rock in the summer of 1878. In the shoot-out that followed, one of Bass' gang was killed outright. Bass was gravely wounded, but managed to escape. He was found, taken back into town, and later died. One account has the 27-year-old outlaw saying "Life is but a bubble, trouble wherever you go" shortly before he died.

Bass may or may not have described life as a bubble, but the Texas Rangers certainly found plenty of trouble wherever they went. Rangers contended with local disturbances that amounted to miniature wars, bloody feuds, lynch mobs, cattle thieves, barbed wire fence cutters, killers and other badmen. The Rangers usually prevailed.

As the turn of the century approached, the reputation of the Ranger as the person required to take care of a situation beyond the means of local law enforcement was well established.

Adjutant General W. H. Mabry wrote of the Rangers in his 1896 report to the Legislature that "This branch of the service has been very active and has done incalculable good in policing the sparsely settled sections of the state where the local officers...could not afford adequate protection."

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

Preserving Law and Order

In the 1890s, Rangers preserved law and order in Big Bend mining towns, tracked down train robbers and even were called on to prevent an illegal prize-fight from taking place on Texas soil. The promoters of the storied Fitzsimmons-Maher bout finally had to settle for staging the boxing match on an island in the Rio Grande.

In 1894-95, the Rangers scouted 173,381 miles; made 676 arrests; returned 2,856 head of stolen livestock to the owners, assisted civil authorities 162 times and guarded jails on 13 occasions.

In 1900, the Frontier Battalion faded along with the frontier; but by July, 1901, the Legislature passed a new law concerning the Ranger service. The force, to be organized by the governor, was created "for the purpose of protecting the frontier against marauding or thieving parties, and for the suppression of lawlessness and crime throughout the state."

Ranger Captains picked their own men, who had to furnish their own horses and could dress as they choose. They did not even have a standard badge.

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

One Riot, One Ranger

The law authorized four Ranger companies of a maximum of 20 men each. The career of Company "B" Captain W. J. McDonald, and a book written about him, added much to the Ranger legend, including two of its most famous sayings.

The often cited "One Riot, One Ranger" appears to be based on several statements attributed to Captain McDonald by Albert Bigelow Paine in his classic book, Captain Bill McDonald: Texas Ranger. When sent to Dallas to prevent a scheduled prize-fight, McDonald supposedly was greeted at the train station by the city's anxious mayor, who asked: "Where are the others?"

To that, McDonald is said to have replied, "Hell! ain't I enough? There's only one prize-fight!"

And on the title page of Paine's 1909 book on McDonald are 19 words labeled as Captain McDonald's creed: "No man in the wrong can stand up against a fellow that's in the right and keeps on a-comin." Those words have evolved into the Ranger creed.

During the first two decades of the Twentieth Century, Rangers found themselves up against men in the wrong as always, but some of the law enforcement problems these officers confronted were as new as the century itself.

Since the days of the Mexican War, Rangers had occasional work to do along the long, meandering Rio Grande, but the emphasis on the river increased in 1910 with the outbreak of revolution in Mexico. Generally easy to ford, the Rio Grande had never been much more than a symbolic boundary. Some of the violence associated with the political upheaval in Mexico crossed the river into Texas.

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

Bandit Raids

On several occasions, Mexican bandits raided into Texas. And at least twice, Rangers returned the favor, making punitive strikes into Mexico. In one battle in 1917, as many as 20 Mexicans may have been killed by Rangers who crossed to the south side of the river.

During this time, the Ranger force was as large as it ever was in its history, and historians who have studied the period agree there was some dilution of quality. After one Ranger raid into Mexico, an entire company was dismissed.

Texas was growing up--the Rangers were part of the state's civil authority, and had to learn to do their work within the framework of the law, no matter the necessary liberties some of their predecessors had taken in earlier years.

Still, the Rangers were not without backing in their efforts to keep the hostilities in Mexico from washing across the river into Texas. Governor O. B. Colquitt wrote Ranger Captain John R. Hughes:"I instruct you and your men to keep them (Mexican raiders) off of Texas territory if possible, and if they invade the State let them understand they do so at the risk of their lives."

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

Bootleggers and Spies

In 1918, the national prohibition law was passed. It gave the Rangers, along with federal officers, another problem to cope with on the border. Many a burro train of bootleg liquor from Mexico was intercepted, and shoot-outs between Rangers and smugglers were not infrequent.

During the first World War, the already large regular Ranger force was supplemented with another 400 Special Rangers appointed by the governor. After the war, on the heels of a Legislative inquiry into the Rangers' operations on the border, the Legislature in 1919 reduced the size of the force to four companies of 15 men, a sergeant and a captain. Additionally, the lawmakers authorized a headquarters company of six men in Austin under a Senior Ranger Captain.

Texas was in a state of transition, and so were the Rangers. Rangers still rode the river on horseback, but they also used cars. The automobile was taking over as the principal mode of transportation in Texas and the rest of the country. And horseless carriages needed oil, not oats. The increased national demand for petroleum fueled a new law enforcement problem for the Rangers.

In addition to their traditional duties, along with assisting in tick eradication efforts, handling labor difficulties and the enforcement of prohibition, the Rangers had to deal with the lawlessness that came with the oil boom in Texas. One of the first places that happened was in a community that years before had been named in their honor.

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

Oil!

The small Eastland County town of Ranger, so named because it had been settled near the site of an old frontier Ranger camp, boomed with the discovery of oil in the area. By 1920, Ranger had a population of 16,000, and a substantial number of those residents were not particularly interested in abiding by the law.

Texas Rangers sent to Ranger, Texas raided gaming halls, smashed drinking establishments, and corralled a wide assortment of miscreants and felons. When Rangers filled the jails, prisoners sometimes had to be handcuffed to telephone poles.

The same story would be repeated throughout the '20s and '30s. Only the names of the towns changed. From Borger to Mexia, Rangers preserved what peace and dignity they could in the wild oil field boomtowns.

The Rangers had greater mobility, but so did the outlaws. Robbers could hit a small town bank and quickly make their getaway. Rangers were given railroad passes, but had to provide their own cars. In the early 1930's, every third Ranger in a company got an $80-a-month car allowance.

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

Frank Hamer

One of the best-known Rangers who made the transition from horse to car was Frank H. Hamer. He first joined the Rangers in 1906. Hamer left the force occasionally to take other law enforcement jobs. But by 1921, he was Captain of Ranger Company "C", stationed in Del Rio. At the beginning of 1922, he was transferred to Austin, where he would spend the next decade as a Ranger Captain.

One of the major problems facing the Rangers during Hamer's tenure as Senior Ranger Captain was bank robbery. The situation got so bad, the Texas Bankers Association offered a standing $5,000 reward for bank robbers. There was one catch--the money would be paid for dead robbers only.

As the Depression took hold in Texas, unscrupulous types began setting up phony holdups, hiring men to rob a bank and then killing them in the act so the reward money could be collected. This was a situation the Rangers could not solve with force. Instead, Hamer went to the press, exposing what was happening. Hamer's move paid off--the banking association's reward policy was changed.

As Senior Captain, Hamer reported to the state's adjutant general, a man appointed by the governor. A governor also could appoint Rangers, or influence a selection. As governors changed, Ranger leadership usually changed. Though history shows many good men wore the Ranger badge in the 1920s and 1930s, the system was rife with politics and ripe for abuse.

When Governor Miriam "Ma" Ferguson took office in 1933, Adjutant General W. W. Sterling resigned his office. Forty Rangers, including Captain Hamer, left with him.

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

Trailing Bonnie and Clyde

But Hamer was not away from law enforcement for long. In February, 1934, Lee Simmons, superintendent of the Texas prison system, asked Hamer if he would track down the notorious criminal couple Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker. Hamer agreed and was given a commission as a Texas Highway Patrolman.

Since 1927, when a force had been created to patrol the expanding Texas roadways, the state in effect had two police agencies.

The young Highway Patrol operated as part of the Highway Department.

Hamer trailed Bonnie and Clyde for 102 days. Finally, Hamer and other officers, including former Ranger B. M. Gault, caught up with the dangerous duo in Louisiana's Bienville Parish. The officers had hoped to take the outlaws alive, but when the pair reached for their weapons, Hamer and the others opened fire. The career of Bonnie and Clyde was over.

For a time, it looked like the Texas Rangers were not going to last much longer than Bonnie and Clyde. Under Governor Ferguson, Ranger commissions were easy to come by, and not all those handed a silver star were men whose character was worthy of the honor. Additionally, Ferguson appointed some 2,300 Special Rangers. A few of those were even ex-convicts.

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

Beginnings of the DPS

The problem did not go unrecognized. The Texas Senate, on September 25, 1934, formed a committee to investigate crime and law enforcement in the state. The committee produced a report in early 1935 that was singularly critical of Texas law enforcement. However, the document also proposed a solution: the creation of a state law enforcement agency to be known as the Department of Public Safety.

A bill was introduced that would create such an agency, which would operate under a three-member Public Safety Commission. The Texas Rangers would be transferred from the Adjutant General's Department and the Highway Patrol would be moved from the Highway Department to form a single state police force.

Some modifications in the law were made by a joint House-Senate conference committee and on August 10, 1935, it became effective.

At about this same time, historian Walter Prescott Webb's classic history of the Texas Rangers was going to press. In a hasty postscript tacked on to the end of the book, Webb made one of the few incorrect predictions of his long career: "It is safe to say that as time goes on, the functions of the un-uniformed Texas Rangers will gradually slip away..." Webb went on to say the new law amounted to the "practical abolition of the (Ranger) force..."

Under the new DPS, the Ranger force would consist of 36 men. Though smaller than it had been in years, the Texas Rangers would have for the first time in its history the benefits of a state-of-the-art crime laboratory, improved communications, and, perhaps most importantly, political stability. In name, the Rangers were 100 years old. With the creation of the DPS, the Rangers would have professionalism to match their tradition.

Tom Hickman, a veteran Ranger, was named Senior Captain of the Rangers. The force was organized into five companies, each headed by a captain.

Within a year of their incorporation into the DPS, the Texas Rangers got national publicity with the opening of the Texas Centennial Exposition at the State Fair grounds in Dallas. The headquarters for Company B was set up in a specially-built log building on the fair grounds. Texas Rangers were seen in newsreel footage in movie houses around the nation.

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

Modernization

Depression-era DPS appropriations were lean, but as the decade of the 1930s ended, the Texas Rangers were on their way toward modernization. Fingerprint and modus operandi files were available for Ranger use at the Department's Camp Mabry headquarters in Austin, and Ranger vehicles were equipped with police radio receivers, though two-way radio would not be available to Rangers until the 1940s. Former Ranger Manuel T. (Lone Wolf) Gonzaullas headed the Department's Bureau of Intelligence, which gave Rangers the benefit of chemical ballistic and microscopic testing in their criminal investigations.

In their early years as part of the DPS, Rangers were furnished a Colt .45 and a lever action Winchester .30 caliber rifle by the state. Rangers had to provide their own car, horse, and saddle, though the DPS issued horse trailers and paid automobile mileage.

For the first time, Rangers had the benefits of in-service training. Weekly activity reports of their activities was required.

The Texas Rangers were part of another agency, but their duties essentially were the same as they had been for years. Rangers were called upon to enforce the state's laws, with particular emphasis on felony crimes, gambling and narcotics. Rangers also were used in riot suppression and in locating fugitives.

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

World War II

During World War II, Rangers provided vigilant internal security in Texas. Ranger duties varied from showing air raid warning training films to tracking down escaped German POW's later in the war.

When U.S. Army Rangers landed in France, the German press thought those commandos were Texas Rangers. This apparently caused considerable anxiety among the German people. The Reich's minister of propaganda eventually had to clarify matters.

By 1945, the authorized strength of the Texas Rangers had been increased to 45 men. Two years later, the force was increased again, to 51 men.

Texas was growing in the post-war economy and so was the parent agency of the Rangers. In 1949, the Legislature authorized construction of a new headquarters building in North Austin. The same year, the DPS bought its first airplane. A Ranger became the Department's first pilot-investigator.

In their first year under the DPS, the Rangers took part in an estimated 255 cases; two decades later, in 1955, the Rangers were involved in 16,701 cases.

Back to Silver Stars and Sixguns

Keeping the Peace

Rangers continued to add to their legend during the 1950s. When inmates in the Rusk State Hospital for the Criminally Insane rioted and took hostages, Ranger Captain R. A. "Bob" Crowder walked into the maximum security unit armed only with the .45 on his hip. Crowder and the leader of the mob had a conversation and the inmates surrendered.

Rangers made national headlines by their quiet but firm presence at various campuses in the state as school integration was for the most part peacefully implemented. When violence seemed possible at the high school in Mansfield, Rangers were sent to the school. A photograph of Ranger Sergeant Jay Banks, reflectively leaning against a tree in front of the high school as students walked into the building beneath a dummy hanging in effigy, was widely published.

Also during the 1950s, Rangers calmed down a violent steel mill strike in East Texas; shut down illegal gambling in Galveston and participated in numerous cases, some sensational, many merely routine investigations.

Ranger activity in these cases usually was documented as briefly as possible. This was Ranger Zeno Smith's report for July 3, 1956: "Wilson County Sheriff requested the assistance of one Ranger in the investigation of twenty-five head of cattle near Floresville. A lengthy investigation resulted in the filing of five complaints and indictments in each case against the suspect who is still at large. 115 hours."